Editor’s Note: Ambereen Khan-Baker, NBCT, teaches AP Language and Composition in Rockville, Md. As an Ambassador for the Montgomery Institute, a partnership between NEA and Montgomery County Education Association, she works with teacher leaders across the country on collaborative problem solving to improve the quality of teaching and learning. The views expressed in this blog are her own.

Have you ever had that feeling where you want to slam your head on the desk because your students just didn’t get it? I think every teacher has experienced that frustration at some point; students may see a concept, but not understand it.

My students in AP English Language have been working on rhetorical analysis all year long. They had to understand the basics first: the structure of an argument, the rhetorical triangle, rhetorical strategies, and the resulting message. But after working on these essentials for a while, my students were still not scoring well on practice essays.

During a unit of study about gender, my students did a close reading of an essay by Stephen Jay Gould, and I thought they understood the text. As I read their rhetorical analyses, I realized I was wrong. Reading essay after essay, I saw that my students struggled to analyze the text. In fact, most of their essays were awful. I stopped reading. My students could identify rhetorical strategies in Gould’s essay, but they didn’t analyze the strategies.

In my head, I reviewed everything I had done during the past week. Based on students’ work as a whole class and in small groups, and the results I saw in their formative assessments, I had thought that they understood what to do. So why wasn’t any of that reflected in their writing?

I was having one of those moments that all teachers face. I felt like tossing their papers aside, but that wasn’t the answer. I had to get past the disappointment and truly analyze my teaching.

I turned to the Architecture of Accomplished Teaching as my guide, a tool I was familiar with from my National Board Certification.

The first step is to examine my students. Who are they? Where are they now? What do they need, and in what order do they need it? I read through the rest of the Gould essays with the goal of identifying the strengths and weaknesses of each essay. By the end, I had a long list for both categories.

Their low scores and lack of understanding meant that I needed to change my instruction. That word, analyze – did my students know what that really means? Did they know what an analysis looks like? Addressing these questions helped me set high, worthwhile goals appropriate for my students at this time.

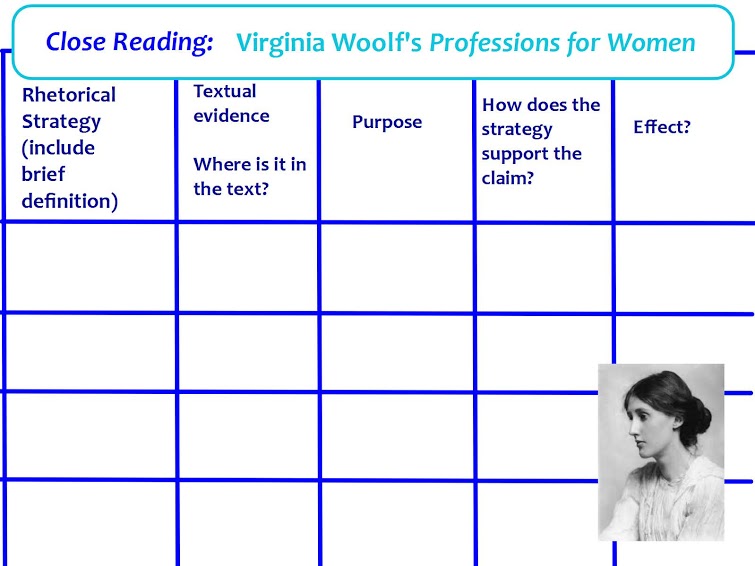

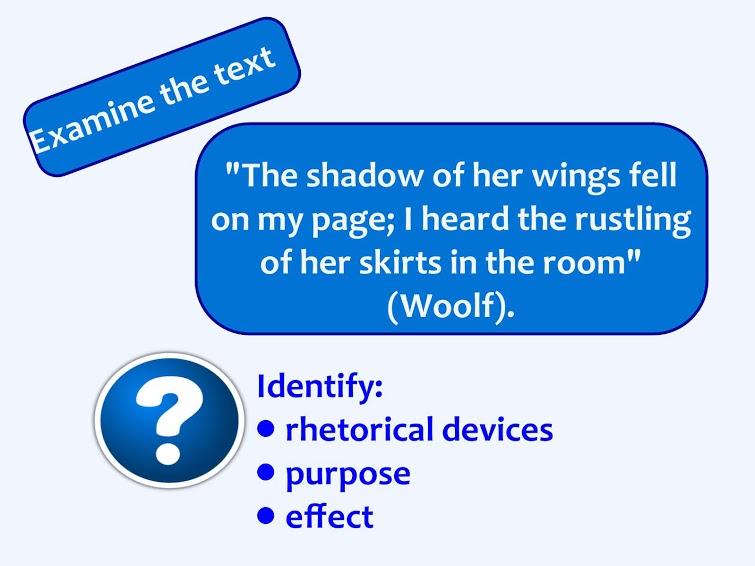

Virginia Woolf’s “Professions for Women” was the next reading we studied, and in preparation for that I redesigned the lesson to address my students needs. The result seemed tedious — a five-column visual organizer to lead from observation to analysis – – and it would take longer than I initially planned. Students complained that that it was too much work, but I told them, “Trust me, this will pay off” – and silently hoped I was right.

On the first day studying the essay, we finished only three paragraphs, but they had analyzed at least seven strategies. The next day, I asked them to reflect on what they had written in their charts so far. I explained, “In your previous essays, I saw that you used information from the first two columns. But you didn’t include information from the last three columns, which is you analyzing the text.”

And that was their a-ha moment. It clicked! “This is an analysis. This is what you include in your essay.”

It was beautiful to see their progress as they improved at pulling out words from the text and explaining the effect those words have on an audience. Eventually, when I evaluated the next set of essays, I was gratified to see that my students had developed a sense of confidence that they knew what they were talking about. No one can take that away.

But the Architecture of Accomplished Teaching is cyclical. Analyzing student work and reflecting leads to more new goals that are appropriate at this time. The work of a teacher is never done! I reflected over this lesson sequence and made changes again, focusing now on helping students craft more effective introductions.

Teaching is a process, similar to writing: Both require self-analysis, being honest about mistakes and shortcomings, and daily reflection on your work. It can be a frustrating challenge at times to confront your mistake or shortcomings, but when we see a group of students experiencing important moments of learning and discovery, we know that those efforts are completely worthwhile.