Editor’s Note: Ray Salazar, NBCT, teaches high school English in Chicago Public Schools and is an award-winning blogger. The views expressed in this blog are his own.

Writing matters to students when they see how words survive in the real world. Yes, our classrooms are the real world. But if the writing in class does not connect to students’ hearts and minds and what matters to them, the lessons can disappear like a Snapchat. I want students to remember the value, the power our writing.

When I worked at a high school in downtown Chicago, I treasured the day (every so often) when I did not drive home in traffic. I’d buy a cup of coffee, put in my ear buds, and zone out on the elevated train all the way home.

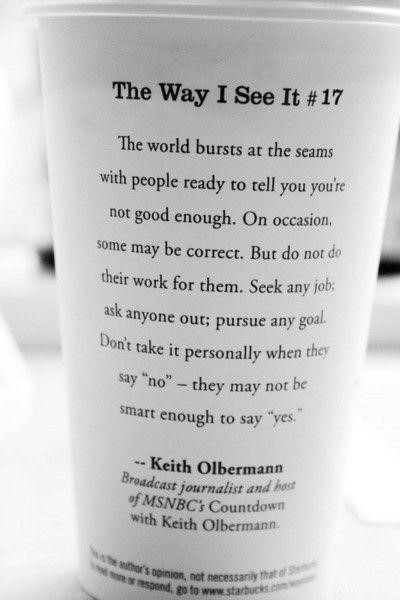

One day, I bought a cup of Starbucks coffee during their “The Way I See It” campaign. Famous or interesting people’s ideas appeared on the sides of cups, to encourage customer contemplation while we sipped. That day on the train, I sipped my drink and stared at the side of the cup:

“There’s something here, “ I thought. This paragraph captured my attention not so much because of the ideas but because of the structures. At the paragraph level, I saw the classic “They Say, I Say” structure I had already taught my students. Then, I noticed the inverted sentence, the cause-and-effect relationship brought about with semicolons, the short sentences, the dash. “Dang! These are all the structures I covered in writing class with my seniors,” I realized. The coffee cup was affirming my real-world approach to writing instruction.

So to end each year, I have students create their own version of this Starbucks campaign. The assignment, titled “What You Wish You Would Have Said,” allows students to resolve, re-define, or reflect on important personal experiences. Aside from deriving some therapeutic benefits, students apply the writing structures at the paragraph and sentence levels we learned in class.

We start by examining Keith Olbermann’s rhetorical decisions. Students then explore their experiences, identifying five situations that remain in their memory because of the mental or emotional challenges that accompanied them. I remind them that the experiences will be made public through writing, so they must decide what they are willing to share with our school community. By the end of the year we’ve established a level of trust that makes students comfortable sharing these unresolved personal situations, generating better writing for this assignment.

They outline the writing using three columns. In the first, they summarize an experience in a few meaningful sentences and establish why it’s meaningful to them. Then they explain why it feels unresolved, and what they wish they would have said. Finally, students search for ways their personal experiences might hold some universal meaning for the audience: why should others care?

Students need freedom to say what they need to say; however, providing some structure and rhetorical constraints can help them as well. Students also incorporate literary techniques we learned throughout the year, and make meaningful decisions about which paragraph structure to use. A climactic one, with the insight at the end, communicates transcendence or catharsis. Placing the insight at the beginning is more straightforward, communicating confidence. I personally enjoy the turnabout paragraphs where the viewpoint shifts in the center. Or they might even generate their own thought-provoking question to evoke contemplation in the reader.

Through our drafting and peer review process, students ask clarifying questions and compliment each other’s ideas as writers. Sometimes, I ask them to respond with a skeptic’s eye: What would someone who does care about this say? Students, after all, need to learn that what we have to say might not matter to some people. Keeping this in mind helps them generate even deeper coffee-cup commentaries.

Finally, students type up the paragraphs, define themselves in a phrase, and we tape them to paper coffee cups.

What I most enjoy about this exercise is seeing the emergence of the philosopher buried deep inside each student’s mind. Even the paragraphs grounded in the most personal of experiences somehow become a universal truth that defies the boundaries of local audience. All of a sudden, students’ coffee-cup ideas become shared wisdom that engages us to feel, to think, to speak, to ask, “What do I wish I would have said?”

This is how I end the year. And on the last day of class, students leave with a souvenir that, I hope, reminds them of the power of writing—always.