As a National Board Certified Teacher, I recognize that accomplished teaching practice begins with knowing my students. The National Board’s Architecture of Accomplished Teaching provides guiding questions around knowing our students’ identities:

Who are they?

Where are they now?

What instruction/support do they need and in what order do they need it?

Where should I begin?

At the 2016 Teaching & Learning Conference, Benjie Howard and Wade Colwell-Sandoval of New Wilderness Project demonstrated exemplary practice in building from a foundation of identity in their session, “Connecting Deeply Across Difference – Engaging Youth as Equity Stewards.” Although the focus of New Wilderness Project is the often-difficult – and therefore commonly avoided – topic of diversity, the presenters, who have become a creative force for arts and social justice education, made the conference room a comfortable space for participants to engage in dialogue around ideas of oneness, otherness and togetherness in our schools.

Howard and Colwell-Sandoval began the session by asking participants to share their narratives around the ideas of beauty and togetherness in a sacred community. The teachers in attendance shared their stories of travel, family and love. Then, Howard and Colwell-Sandoval connected the group’s narratives to the themes of their hip-hop and folk inspired song-stories. Next the audience had the opportunity to experience portions of their Youth Stewardship workshops.

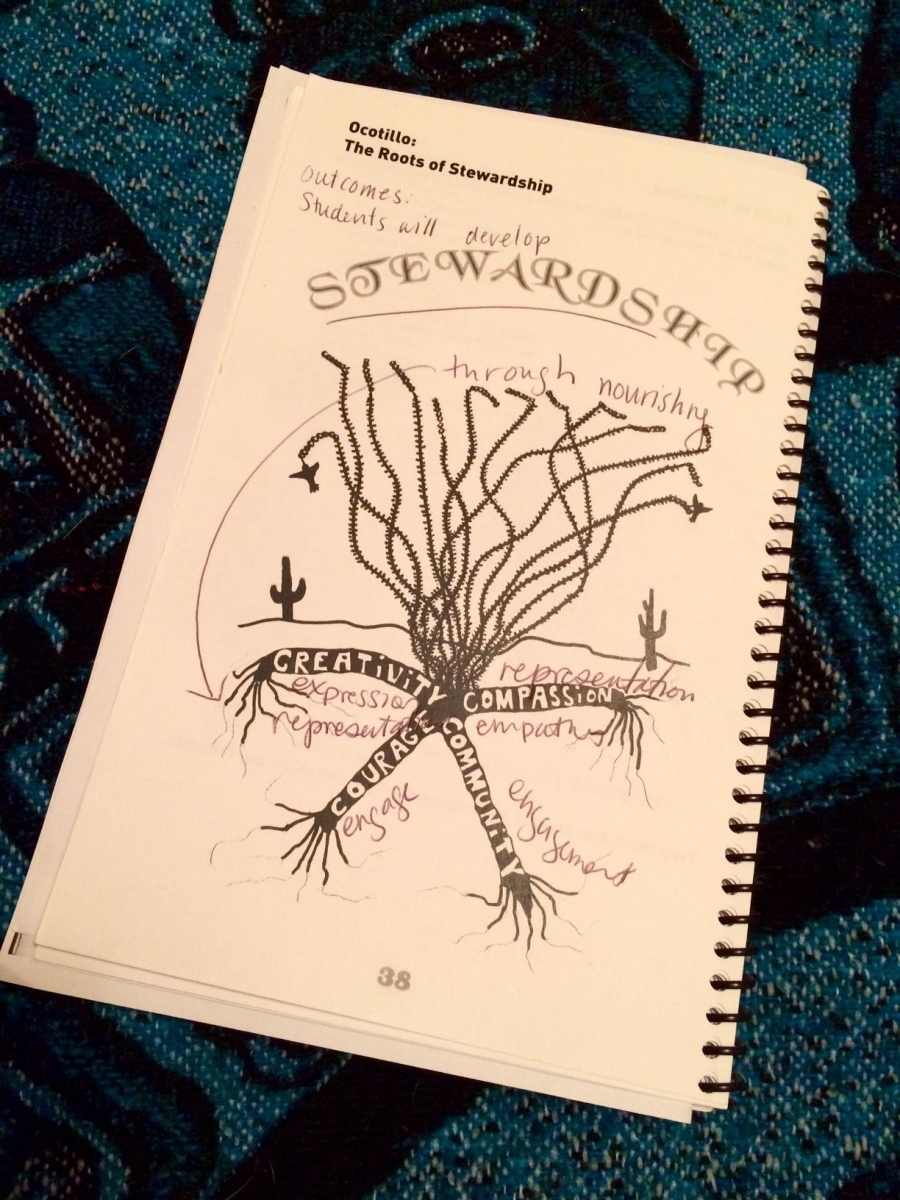

New Wilderness Project defines stewardship as action that arises from caring and informed relationships to one’s community, and a vision of power through collaboration. Their work uses the symbol of the ocotillo tree as a metaphor for stewardship.

For most of the year, the ocotillo tree blends into the parched landscape of the Arizona desert, its branches appearing as a mere bundle of dry sticks. However, the ocotillo will bloom into a spray of rich red flowers when its roots are nourished by rain. Unlike many desert plants and shrubs, the ocotillo does not just bloom during certain seasons; it blooms whenever it is nurtured by the rain.

For most of the year, the ocotillo tree blends into the parched landscape of the Arizona desert, its branches appearing as a mere bundle of dry sticks. However, the ocotillo will bloom into a spray of rich red flowers when its roots are nourished by rain. Unlike many desert plants and shrubs, the ocotillo does not just bloom during certain seasons; it blooms whenever it is nurtured by the rain.The ocotillo offers a useful representation of stewardship. The roots of stewardship are creativity, courage, community and compassion. These roots are nourished by people and communities identifying their aspirations. When aspiration nourishes the roots, different ways of being, thinking, and taking action, all open up like the flowers on the ocotillo branches, as stewardship blooms in its full glory.

I’ve been pondering this metaphor, and see it as a tool for reflecting upon my journey as a teacher-leader. First and foremost, I have recognized a need to view myself as someone who aspired to stewardship of my classroom. The quicker, more familiar path to leadership involves taking a dominant role in relationship to students and colleagues. Instead, I’m reminding myself that true transformative teaching practice comes from acting in the best interests of the community.

In meditating upon the roots of stewardship, I came to assess my personal strengths and areas of need. I am strongest in my creativity and courage. I believe that any problem has a solution that can be identified through creative problem solving, and I am courageous because I am never afraid of the consequences of my actions when I am acting upon my values and best judgement. For example, at an event where I spoke in front of district leaders, I was not afraid to share the truth that ESL classes were not being offered as they should have been in the school where I worked. This courage was guided by advocacy for my students and collaboration with teachers and students, and I knew the risk was that I might anger someone, but the reward is that ESL services in our district are actually improving. Other strengths include engaging my school and professional community – through blogging, participating in community meetings and events, and forging personal connections grounded in my passion for working with culturally and linguistically diverse students.

The process of reflection is not just about noting my strengths; my weakest area is compassion. While I have endless energy for academic activities and advocacy, I can be impatient with others who do not seem to possess the same energy, or who seem hesitant to take actions addressing necessary improvements. I am working hard on growing in this area, even trying out some tools such as a “meta-moment” and a mood meter app that I learned about at the Teaching & Learning Conference.

I can name the branches that my ocotillo has grown. My students have improved their expressive writing and entered an essay competition on youth violence, and they crafted and delivered presentations about the life of Malcolm X. I have practiced stewardship by writing and publishing my truth on various blogs, making presentations, and creating a collaborative blog on writing instruction for ELL students with and without disabilities.

I aim to continue growing branches on my ocotillo by developing my compassion – the ability to listen to, reflect upon, and respond to the needs and aspirations of others. Benjie Howard and Wade Colwell-Sandoval’s presentation helped me to forge connections with like-minded educators, and also to aspire to effective stewardship, like the growth of a beautiful ocotillo in my teaching soul. I plan to revisit this metaphor when reflecting on my growth as an educator, a leader, and a human being.