Effective whole-class discussions are part thoughtful planning and part luck. Sometimes an instructional approach works so well that we expect the same results the next time we use it. And sometimes, that works out. Other times, we wonder, “What the heck happened?”

I thought I had found another consistent way to engage as many of my students as possible in whole-class discussions. It worked really well last week. But this week, I got crickets.

Last week, we listened to a podcast about the concept of success – This American Life’s “Three Miles.” Students annotated, reflected, and shared in small groups. I also started using Padlet, an application that allows students to text a response on an electronic bulletin board. My students generated interesting commentary and rich conversations.

But this week, when I tried the same approach after we read “What it’s like to be a poor kid at an Ivy League school,” the conversation dwindled. The contributions on the electronic bulletin board seemed repetitive. Few students participated. We had dead air.

I had broken up the article into two page chunks for the discussion. During the first of our 45-minute blocks (after a quiz), students worked through the first two chunks—grudgingly. The bell rang. They went to lunch. This gave me 45 minutes to eat and figure out how to salvage this lesson before they came back.

Think, Ray. Think. What’s made students talk? Maybe there’s some emotional reaction they’re not sharing.

I looked at the text again and asked myself: How is this text telling me it needs to be taught?

I saw four students profiled. So that’s how I needed to chunk this—not by pages or even sections. What was missing from this whole-class discussion was the sense of emotion. I decided to make this conversation about an expository article into something more debatable.

Before my class returned from lunch, I came up with a rating scale for my students to apply to each individual profiled in the article.

What’s your reaction to this student’s struggle?:

4 – strongly sympathetic

3- sympathetic

2 -skeptical

1- strongly skeptical

I didn’t give them a neutral option. That’s the comfortable place to go, to engage without engaging.

They came back from lunch. I felt ready. Each group focused on one profile for a few minutes, making sure to pull out textual evidence of that student’s struggle.

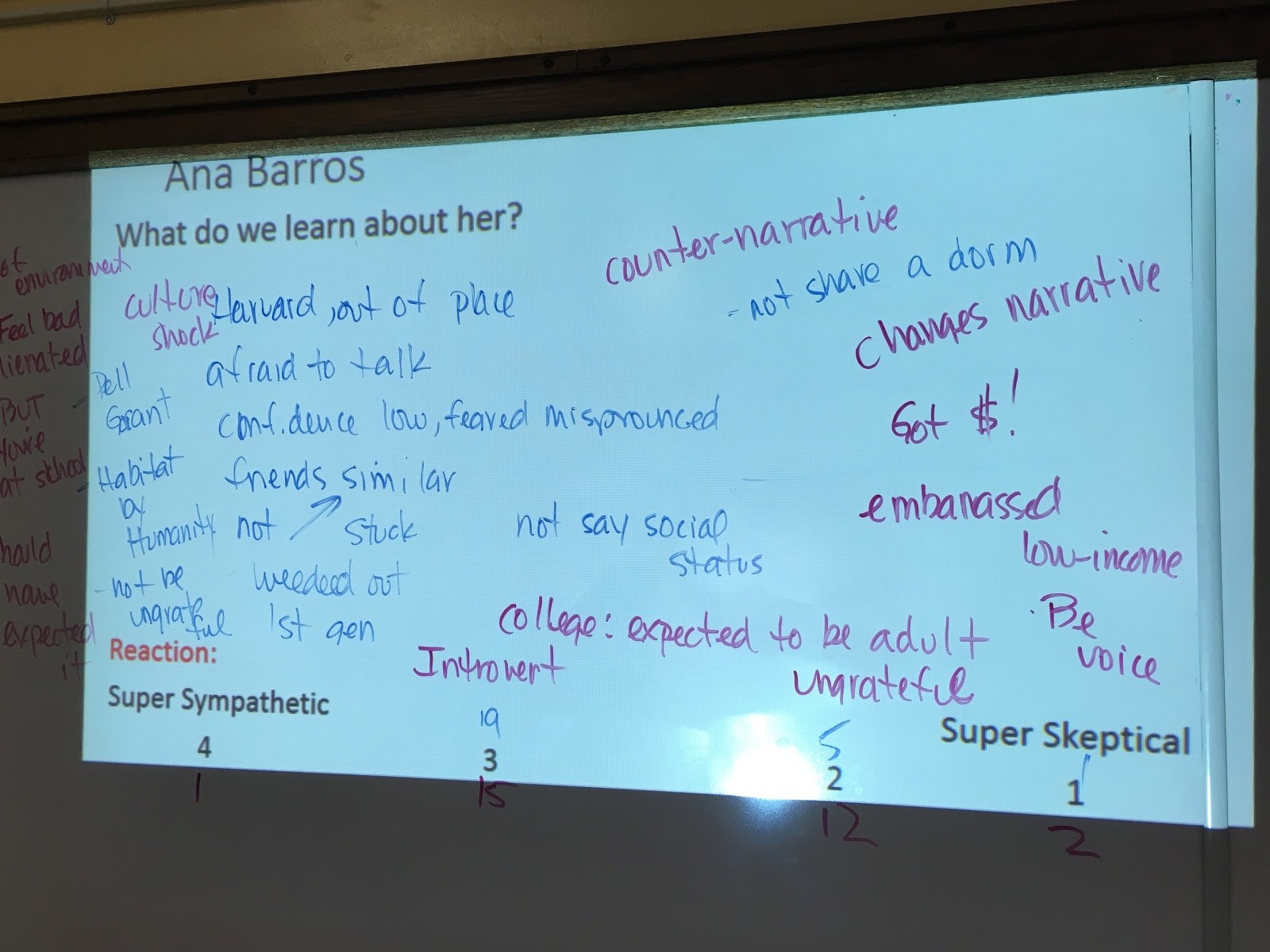

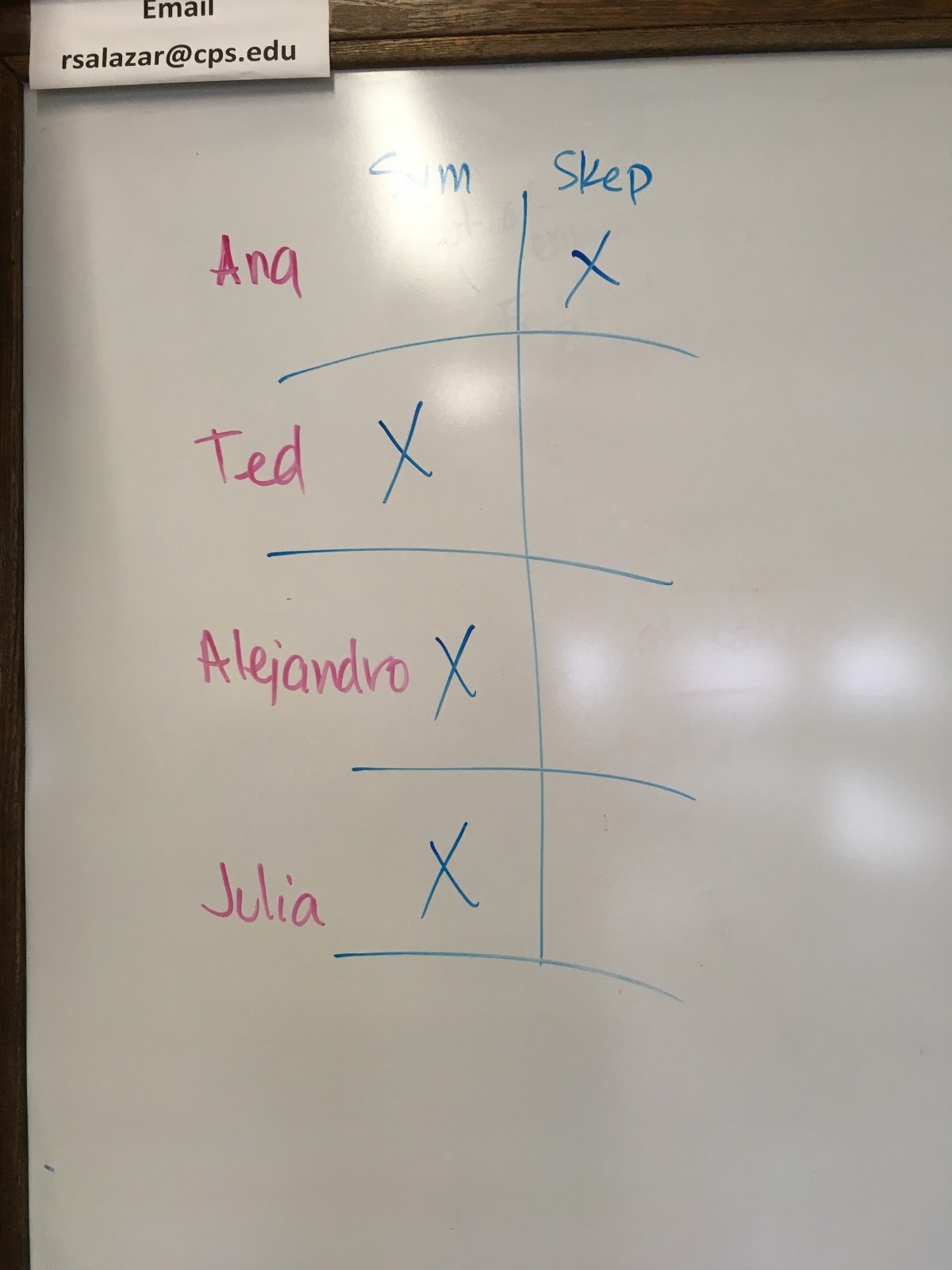

As a class, we then focused on one student at a time. With active participation from my class, I could fill up the board quickly with elements of each profile. And then my students rated their emotional reaction to that struggle.

This rating became the conversation.

When we looked at Ana Barros, we discussed what kept students from being strongly sympathetic to her struggle; no one gave her a 4.

One student said: “I feel bad for her about how she felt being on campus, but I don’t necessarily feel sympathetic. You’re at the school. Take advantage of it. Don’t be scared to do things.”

Another students said: “She should have expected the culture shock.”

Someone else said: “I kind of sympathize with her being in this new environment. At the same time, she’s in college and supposed to act like an adult. An adult is not supposed to be led by the hand.”

A skeptical student said: “She’s basically embarrassed about being low-income. But she shouldn’t be embarrassed. She’s proving she can be at that level.”

To this, a student added: “When people from her neighborhood see her finishing college, it changes the narrative for everyone else.”

After we discussed each student in the article, I asked my students to rate the struggle again. There was always a change in the ratings. We briefly discussed students’ rationales for their ratings as well.

At one point, when many in the class criticized one of the low-income, Ivy-League students for not self-advocating, one student–the only one who expressed sympathy in this case–said, “But it’s criticism like that that prevents people from asking for help.”

That made all of us think.

The conversation about this article continued for thirty minutes, and went by quickly. Some students shared obvious info from the text. All students expressed their opinion of each student’s struggle in the survey. Many students agreed or disagreed with their classmates, offering sound, sincere, and considerate comments.

Phew!

This article presented too much of an opportunity for students to raise their consciousness about being at an elite college, about living and studying somewhere far removed from their everyday context. I couldn’t let the experiences in this article fade away.

I do wish they would have made more connections with the other texts we’ve studied, like, “How not to talk to your kids” and “Best in class.” But the conversation proved productive, especially when I closed the exercise with a survey to gauge their general reactions.

Most students felt skeptical towards the first student presented in article. But most felt supportive of the others.

So our closing reflection question was this: Why did the writer decide to open the article with an experience most readers would feel skeptical towards?

One honest student bluntly asked: “Wait. They planned it that way?”

We needed some comic relief. “Yes, yes they did,” I said chuckling.

The challenge with whole-class discussions is that students can easily disengage. They might look like they’re listening. They can appear to be in deep contemplation. They might share ideas publicly. They might not. So how do we ensure we engage as many students as possible? And how do we get them to engage with each other?

This approach tapped into students’ emotional reactions and kept them grounded in the text.

It worked so well this time that I have to conclude it’s worth another shot. Will it work every time? Who knows?