At the beginning of the year, my Chicago Public Schools high-school students expressed lots of frustration because I didn’t write any comments on their first major essay. “You need to give us feedback,” they demanded. Some doubted I read their essays because I didn’t make a mark.

I explained that one of my goals as a teacher has become to build my students’ independence, thus fighting against the image of students stretching out their hands like fans at a rock concert, fluttering their paper for the teacher’s attention. I also fight against the ugly co-dependence that arises when teachers feel they must review every sentence, respond to every main idea in order to feel accomplished.

I told my students that somewhere I read, “Whoever does the thinking does the learning. So if I’m writing down ways you can improve your essay,” I continued, “guess who’s doing the learning?”

A few reluctantly said, “You.” Most of them glared at me still wanting my written comments on their paper.

Feedback, I’ve learned to explain to students, is not the teacher telling students what to do. Feedback is creating learning experiences that allow students to reflect on their progress based on some explicit guide, or model, or expectation.

Rubrics? Meh. Those are teacher-directed documents. Rarely do they, alone, provide the information that helps students move beyond superficial conclusions about their process, their depth of thinking, their opportunities to grow. Too often, student-friendly rubrics come off as simple checklists, not reflective guides.

A couple of months ago, I came across an article about feedback from the Harvard Business Review titled “The Feedback Fallacy.” In it, the authors highlight how giving people feedback rarely brings about any significant changes. They discuss how–when we receive feedback–our brains shift into fight or flight mode. Furthermore, the authors explain, focusing on weaknesses doesn’t increase our strengths.

This made me consider that if all we did was tell students all the great things they did, that wouldn’t help them grow either.

The article explains how “learning happens when we see how we might do something better by adding some new nuance or expansion to our own understanding.” Hence, we need to provide students with more than rubrics.

Furthermore, the article states, “learning rests on our grasp of what we’re doing well, not on what we’re doing poorly, and certainly not on someone else’s sense of what we’re doing poorly.”

If students only hear what we—the teacher—think they’re doing poorly, learning becomes a game. “Well, what does the teacher want?” students begin to conspire.

So, instead of dedicating hours and hours writing individualized feedback on each students’ papers, I devote time to figuring out learning experiences that will help students reflect on their work throughout the process and after they submit final essays.

1. Students need real-world sample texts as examples to follow

Because students were going to write profiles (first of themselves in the third person, then of someone else), they needed to read well-written profiles. Whatever we teach, students need to learn from texts that do what they’re going to do.

Teachers, of course, need to believe in students’ capabilities to create subject-relevant examples of learning that can live and breathe outside the classroom. If all students are doing is looking at samples of someone else’s successful answers on some test, that’s a problem (and another blog post).

Early this school year, my English students chose a profile about Joe Rogan, Steve Jobs, our CEO, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ivanka Trump, or football player Michael Bennett.

In one of their readings (they did a total of three) they looked beyond what the writer included and began to unravel how the writer communicated.

- How are we supposed to view the person profiled?

- How does the writer establish that bias in the opening section?

- Is the initial bias maintained or does it change?

Then they dug in deeper:

- How does our engagement with the person profiled intensify?

- In the high point of the text, how does the writer use quotes, description, sentence structure, word choice to show the intensity of the shift before the conclusion?

- How does the writer make us feel something at the end of the reading?

- How does this contrast with the feelings evoked in the beginning?

All of this gave them rhetorical moves, strategies, tools they could use to write well—and to earn an A.

Shifting conversations from “What happens here?” to “How is this structured?” gives students insights into how they can use these texts as models during their own process as they demonstrate their own learning.

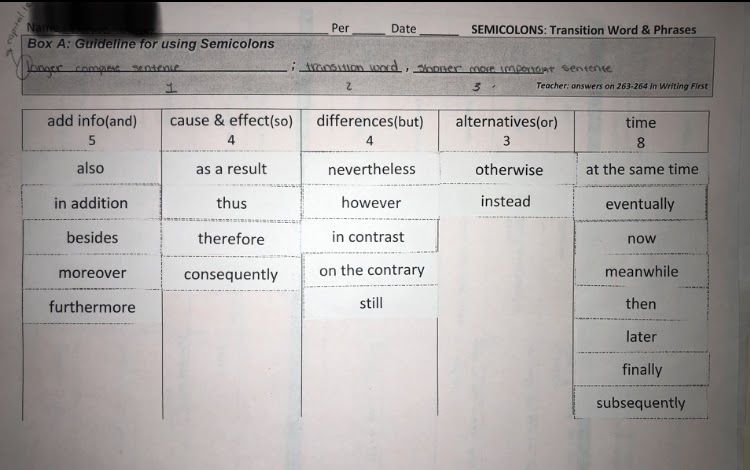

Here’s the organizer we created with information from Writing First to help us understand semicolons:

Rhetorically, I teach my students, the first sentence needs to be longer; the second needs to be shorter. This structure adds emphasis to the info after the semicolon.

When I review their exit tickets with semicolons and mark a sentence incorrect, they then get an opportunity to look back at this resource to struggle through finding their mistakes. If they still can’t figure it out, I step in to help them.

The observations and insights they capture in their annotations and reflections serve as a resource they can refer to as they draft their own pieces of writing and attempt to mirror the professional writer’s moves.

2. Students need to compare and contrast their text with the assignment

A given here is that students receive clear guidelines that allow them to demonstrate their knowledge within some challenging constraints while allowing them freedom to express their ideas.

Sometimes, the most valuable feedback experience we can provide for students involves double-checking their work against the prompt.

Did you begin with a philosophical idea to enter this conversation and present your view? Put a checkmark if you did.

How many connections did you make among the texts we studied? Number each one.

How well-developed are your ideas? Highlight all of the sentences that come from you.

Did you incorporate the sentence structures we learned? Put a star by each one.

This helps my students understand why they earned an A or B or C or D or F. If it doesn’t, these reflections help us have a more meaningful conversation.

I also provide students samples and we identify the strengths of that student’s work. “Now, take a look at that part of your work. Did you do what this student did? If you did, you should be in the A or B category. If not, what’s missing?” I ask them to reflect.

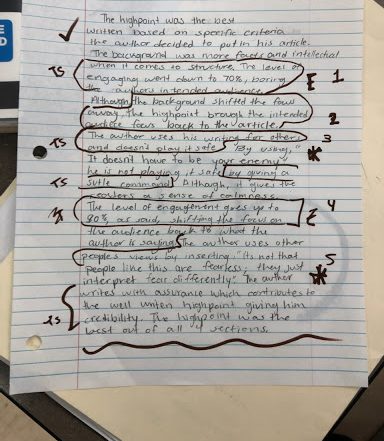

Here’s one accomplished piece of timed-writing a student annotated based on our prompt-reflection exercise.

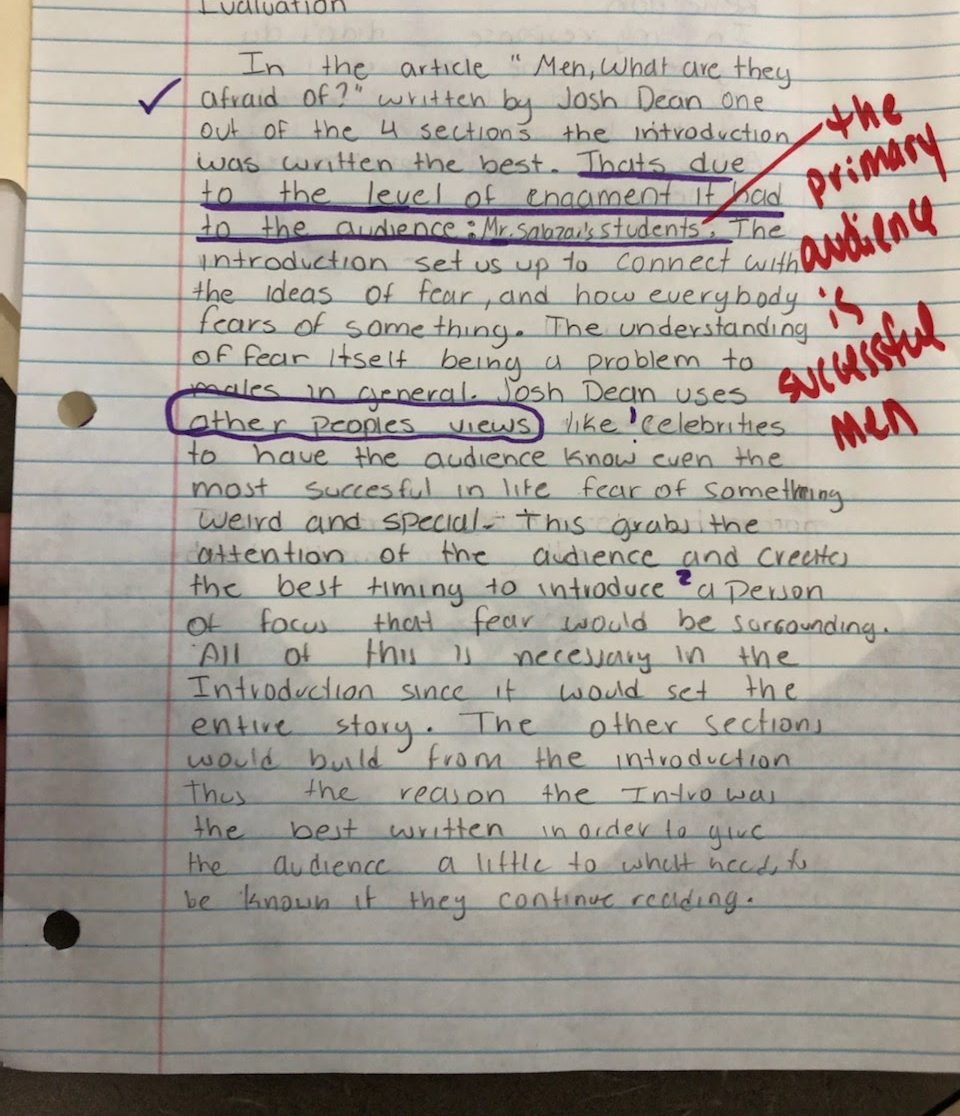

Here’s a piece that did not meet the expectations of the prompt. I also clarified a misunderstanding regarding the primary audience about this article from GQ Magazine.

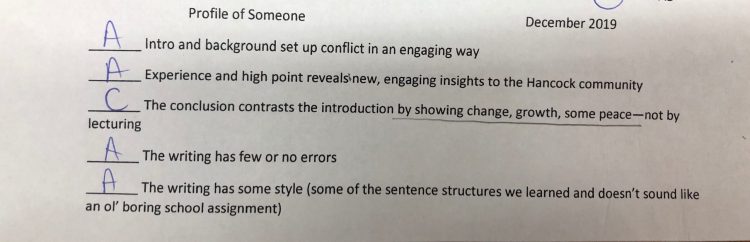

3. Students need general concepts of what grades mean—not rubrics.

This is why I’ve become opposed to detailed rubrics with degrees of performance. These become so task specific that students find it difficult to transfer their learning from one task to another.

Instead, students need opportunities to reflect on general concepts they can remember to transfer over to their next assignment.

I followed the lead of my Chicago public school’s science department and adapted some general language that can be modified for content, or structure, or style.

- An A exceeds the standard and can be used as an example for many other students to follow.

- A B meets standards and there are only a few areas for improvement.

- A C shows basic mastery or a predictable response.

- A D shows some significant misunderstanding or something major is missing.

- An F is an unacceptable attempt or no attempt.

If the pieces of writing, the mentor texts, serve as examples of an A, then students can find ways to mirror these accomplished pieces in age-appropriate ways. While the sentence structure may be highly elevated in some mentor texts, students can look for ways to show sentence variety or try to copy thoughtful uses of punctuation and syntax. They can find moves to copy based on their individual reading experience, reflections, and conversations in class—not because I tell them what to do.

4. Students need discipline-specific guidelines that define success

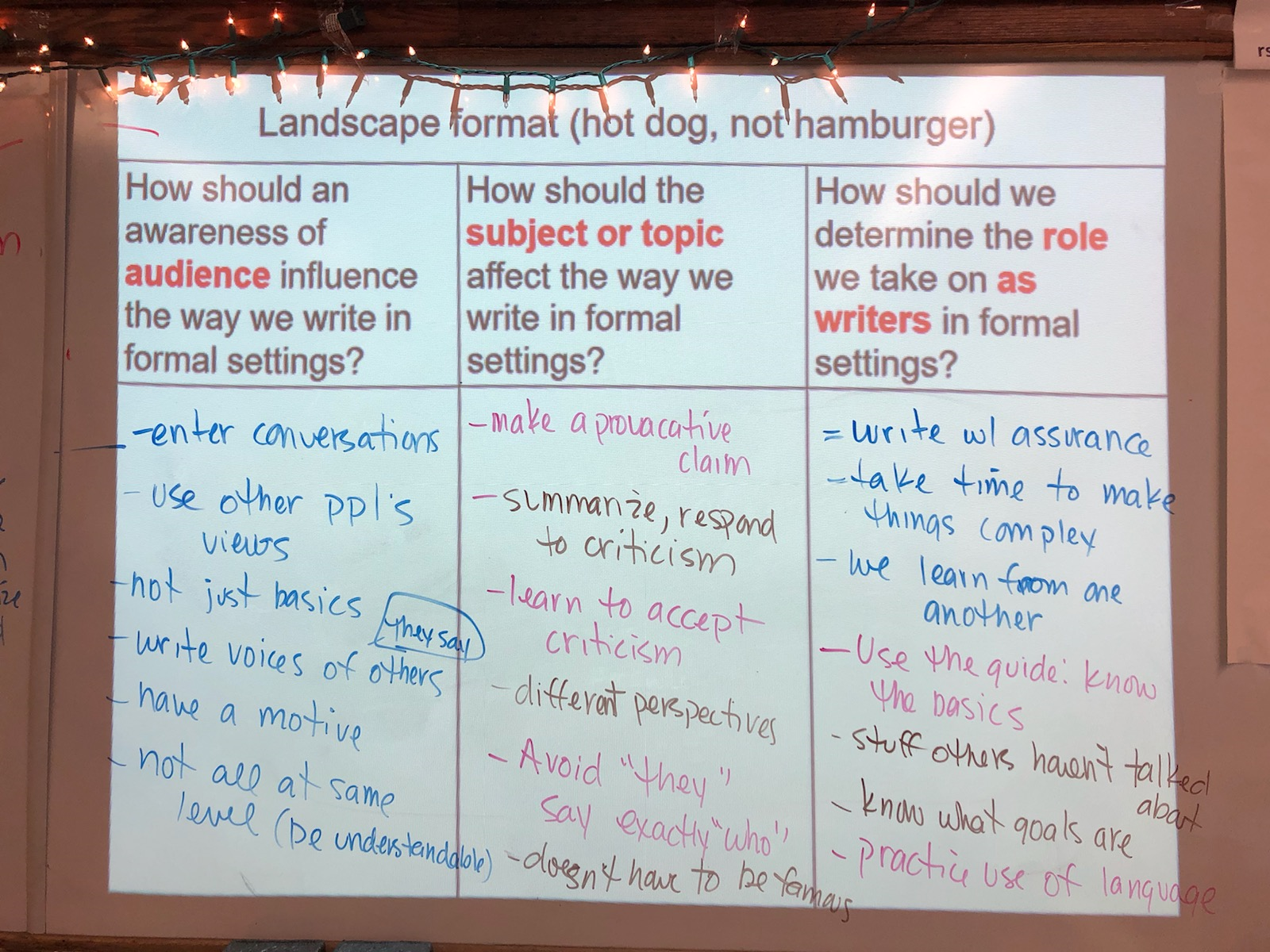

One of the most valuable texts I used with my writing students is They Say, I Say, a guide to academic writing. As students read sections of it, they document what academic writing is supposed to do. This becomes a guide they can follow as they draft and revise their work. Most importantly, this pushes their struggle away from “What does the teacher want?” to a more important question: “What does this discipline demand?”

In one quick writing workshop conversation with a student, she told me, “But I don’t know how to start the section about the past.”

I asked her to find her chart with the notes from They Say, I Say. “What moves can you use from there?”

“Oh,” she snapped. And the move became clear.

We need guiding principles our students can use whether we teach writing, math, history, P.E., or art. This teaches students to reflect on their progress and ask themselves, “Am I proceeding appropriately?”

Most importantly, students need to learn to use resources like those mentioned above to turn to each other and engage in discipline-specific, academic conversations. This way, we build their independence and confidence in their ability to use the resources and experiences we provide to learn.

I know students still need to hear from me.

So when we devote class time to drafting, I talk with each student quickly about one issue they’re having or concerned about. My feedback here usually involves re-directing them to something we read so they can reflect and make a decision about what to write or how to write it. Often, all they need to hear from me is an affirmation that what they’re doing is good.

And when they give me feedback on each major assignment, I read over and over that these experiences help them become better writers–without depending on me.