The surge in media coverage on the COVID-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter protests overwhelmingly exposes systemic oppression within our country’s institutions. Of such institutions, public education embodies an oppressive system adversely impacting various ethnic subgroups. Studies indicate that inequitable structures in education sustain negative outcomes for Black male students, especially those with disabilities (Booker, 2018). Inequitable structures include, (but are not limited to), biased standardized testing, a lack of resources, inexperienced teachers (Harris, Ingle & Rutledge, 2016). Distant learning amplifies structural inequities for disadvantaged African American male students with ADHD. The inequity of e-learning is amplified by the scarcity of technological equipment, and by the ineffectiveness of implementing web-based lessons for Black students with disabilities.

It is time for change. Instead of exacerbating these pre-existing inequities, virtual learning could increase opportunities for this vulnerable student group to advance academically. Can educators take this opportunity to advocate for the most vulnerable of students and incite change to an inequitable system?

Prior to the COVID-19 school closures, my student was on an educational trajectory that mimicked the school to prison pipeline pathway. T was often observed disengaged from class lessons; and, at times, disrupted classmates’ learning with aggressive behavior. In spite of interventions rendered from school, family, medical and community stakeholders, T struggled to meet the requirements to achieve. He incurred 11 school suspensions within 6 months during the 2019-2020 school year and exhibited similar behavior and suspension rates in his previous school years. The School Student Services Team recommended an increase of supports to his special education services plan to meet his emotional and behavioral needs.

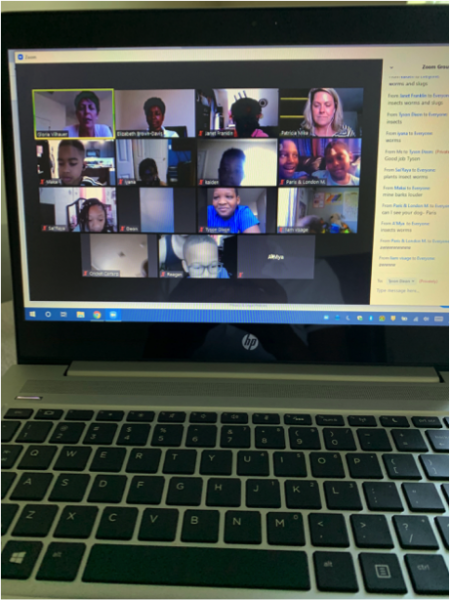

During the COVID-19, stay-at-home order, T transformed from a disengaged struggling student into a vibrant, energetic nine-year-old, eager to learn through a virtual platform. To my surprise, I observed my nine-year-old student attentive, compliant, and happy. Each morning, T woke himself, got dressed, made his own breakfast, and logged into the Zoom meeting on his own. He participated in all of the e-learning activities, including typing into the chat box when prompted. T interacted appropriately with his classmates on the virtual platform. He completed the asynchronous assignments independently after each Zoom meeting. What altered T’s academic trajectory from a failing student to an achieving student during the shift to remote learning?

From my observation, there were key aspects leading to T’s new-found success with remote learning. The first factor leading to T’s success was the accessibility of the lessons. Once T received his laptop, remote learning afforded T opportunities not availed during the traditional school day. Secondly, the cancellation of standardized testing allowed the freedom to provide T with individualized instruction to meet grade-level standards. Lessons were flexibly designed to meet his learning style and paced appropriately to his attention span. Finally, a culturally responsive pedagogy was infused in T’s e-learning. During the Zoom learning sessions, T’s grandmother posed as a role model teacher and made personal connections to the lessons. Could a virtual learning model with the flexibility to accommodate students with varying exceptionalities assist in closing the achievement gap?

From my observation, there were key aspects leading to T’s new-found success with remote learning. The first factor leading to T’s success was the accessibility of the lessons. Once T received his laptop, remote learning afforded T opportunities not availed during the traditional school day. Secondly, the cancellation of standardized testing allowed the freedom to provide T with individualized instruction to meet grade-level standards. Lessons were flexibly designed to meet his learning style and paced appropriately to his attention span. Finally, a culturally responsive pedagogy was infused in T’s e-learning. During the Zoom learning sessions, T’s grandmother posed as a role model teacher and made personal connections to the lessons. Could a virtual learning model with the flexibility to accommodate students with varying exceptionalities assist in closing the achievement gap?

As state and local school officials struggle with a new school year, it is my hope that we use the experience from the COVID crisis to address the inequities in education for Black male students with disabilities. Whether students engage in the face-to-face traditional classes or virtual learning, learning models should consist of the flexibility to accommodate the needs of the vulnerable students. Inequitable structures in education may be repudiated by reinventing schools comprised of a “hybrid” model, combined with culturally responsive pedagogy. If implemented appropriately, reimagined school structures pose to disrupt the systemic oppressive school to prison pipeline pathway. My student can be seen as a vibrant, energetic nine-year-old Black male student on the college and career readiness track. On the pulse of this moment, can teachers drive the necessary changes to establish an equitable school experience for AA male students with disabilities? I believe we can, and we should.

References

Booker, R.L. (2018). Discipline and the school to prison pipeline. American School Board Journal. Retrieved from https://www.nsba.org/newsroom/american-school-board-journal/as just-February-2018/online-only-discipline-school-prison.

Harris, D.N. Ingle, W.K., Rutledge, S. A. (2016). How teacher evaluation methods matter for accountability: a comparative analysis of teacher effectiveness ratings by principals and teacher value-added measures. American Educational Research Journal. 5(1)73-112.